I was honoured to be invited to speak at ResearchED Rugby on the 1st July 2017. I had the sexiest title (see above) on the conference programme but was unfortunately up against the likes of Oliver Caviglioli and Jake Hunton… Still, I had a good crowd who were witness to my first ever presentation at a conference. Thank you for coming and for laughing in the right places!

I was honoured to be invited to speak at ResearchED Rugby on the 1st July 2017. I had the sexiest title (see above) on the conference programme but was unfortunately up against the likes of Oliver Caviglioli and Jake Hunton… Still, I had a good crowd who were witness to my first ever presentation at a conference. Thank you for coming and for laughing in the right places!

In this post I’ll share Part 1 of my presentation which centred around my views about KS3 in recent years and my arguments for the re-prioritising of it. I’ll follow this with Part 2 in which I’ll share details of my KS3 curriculum redesign and where we’re going with it next year.

The Wasted Years?

I started by talking about this report, published a couple of years ago. HMI commissioned a survey to get an accurate picture of whether KS3 was providing sufficient breadth and challenging and helping students to make the best possible start to their secondary education. A bit of a spoiler alert if you’re yet to read it but the short answer is that they didn’t think it was – they concluded that typically there is a lack of challenge and a lack of quality teaching at KS3.

The report suggested that weakness in teaching and pupil progress reflected the lack of priority given to KS3 by many school leaders – 85% of the senior leaders interviewed said that they staff KS4 and KS5 before KS3 which increases the chance of split classes and students being taught by non-specialists.

I don’t imagine the findings were much of a surprise to many of us – KS3 has historically been given low priority in schools. It’s certainly been my experience that the KS3 curriculum has been pretty poor and has not provided students with sufficient breadth and challenge – too often, in my experience anyway, too much of KS3 time is spent keeping students busy or having fun.

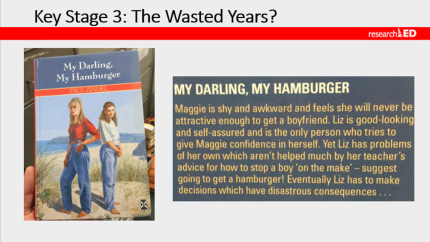

My Darling, My Hamburger

At this point I shared this image of the cover and blurb of ‘My Darling, My Hamburger’. You may be wondering why on earth I did that but read the blurb and let me explain… I came across this book a couple of years ago when I was working at a school in Bexley. For whatever reason, I took it upon myself to clear out the stock cupboard (a Herculean task given what hoarders English teams tend to be…). The cupboard was filled to the brim with absolute rubbish – there were several class sets of this beauty.

Presumably the rationale for teaching ‘My Darling, My Hamburger’ at KS3 was that it was, in its day, an ‘engaging’ text. Now whilst I don’t imagine anybody is still teaching it (please get in touch with me if you are) I think it exemplifies many of the questionable texts choices included on KS3 curriculums up and down the country. Why are we wasting lesson time on this dross? Why are we picking texts based purely on how engaging or how relevant they are?

I think our job is to teach great works of literature however challenging that might be. Our job is to take Hardy or Bronte or Shakespeare or Dickens and make that accessible for all our students. If it was good enough for us and it’s good enough for students in private schools or grammar schools then it’s good enough for all of my students. Because of course these great works of literature are relevant to everybody – they’re part of our cultural heritage and I want my students to have cultural capital; they’re not going to get that from reading books that are the modern day equivalent of ‘My Darling, My Hamburger’ in lesson time. David Didau writes convincingly about the importance of cultural capital here.

Fun Fact – Grainne Hallahan (@heymrshallahan) discovered that ‘My Darling, My Hamburger’ is the text they’re studying in Dangerous Minds before Michelle Pfeiffer comes along. My new motto: if it isn’t good enough for Pfeiffer it’s not good enough for me!

I then shared an example of a typical KS3 curriculum map, like the one in place before I took over as Head of English, in which each half term has one focus e.g. year 9s might study non-fiction and media texts for 6 weeks followed by 6 weeks on poetry. I have quite a few issues with the half termly unit model:

- It’s quite a challenge to study a full text in just six weeks which is why many teachers resort to teaching from extracts of Shakespeare plays or longer novels

- Students will probably get one ‘go’ per year on a key skill e.g. in year 7 they might do a poetry analysis unit but then not get another opportunity to analyse poetry until year 8

I also think there’s a flaw in encouraging teachers to select their own texts for study. Firstly, there’s a workload issue in that you end up with each of your team having to plan and resource their own six week units – surely it’s better for teams to share and enhance each other’s knowledge of set texts? Secondly, I think it allows for a worrying teacher lottery in which students in the same school get a very varying quality of WHAT they are studying.

O brave new world that has such new GCSEs in ‘t!

Now it was perhaps not with quite the same delight with which Miranda marvelled at Ferdinand that we welcomed the specification changes but the new GCSEs did give us a unique opportunity or excuse to completely shake up KS3.

In my Tempest analogy here the shipwrecking at the start of the play represents the death of iGCSEs, coursework, 20% of the final grade being made up by Speaking and Listening and the end to open book exams – all of which represents a real challenge to both teachers and students which makes redesigning the KS3 curriculum an imperative if we want our students to be successful at GCSE and beyond. Us teachers are those poor souls on the shipwreck (Trinculo perhaps…) desperately swimming through the stormy seas to reach a strange and unfamiliar land.

The irony of being a teacher is that we most of us don’t like change – we are creatures of habit who mark with the same pen, drink from the same mug (if it hasn’t gone missing or been stolen) and sit in the same seat in the staffroom. And yet, the most abiding feature of teaching, certainly of my teaching career, is change. Just in the time I’ve been teaching we’ve had: the year 9 SATs scrapped; traditional coursework replaced with controlled assessment; APP coming in and going out; the death of national curriculum levels; changes to the GCSE and A Level specifications and so on and so forth. We’ve been washed up on plenty of shores before now.

But, I think if we keep the main thing the main thing (focus our efforts on key knowledge and skills) and design our KS3 curriculum accordingly we can weather the change and survive the stormy seas of new Education Secretaries wishing to make their mark. I came to the realisation, if we extend the Tempest analogy, that Michael Gove is Prospero and he’s the one who’s brought us here…

Here’s the man himself taking his grenade to everything we’d got settled with. I never thought I’d say this but perhaps I am grateful to Michael Gove for bringing about these GCSE changes because it’s really forced us to raise our game at KS3.

The Foundations

KS3 forms the foundations for future learning. If we get things right here then we’ll have students moving up to year 10 and beyond with a good knowledge and skills base which will mean they are more likely to succeed. It’s symptomatic, I think, of bad KS3 design that we end up throwing everything and the kitchen sink at intervention and revision sessions at KS4. Not only is it often too late for many students by then but we’re also working both students and teachers to the point of exhaustion. We need to play the long game. KS3 is AS important if not more so – to think otherwise is short-sighted. There’s no point in me trying to build a house on sand.

So… if you’re in the process of redesigning your KS3 curriculum I think you have to start by knowing what foundations you want your students to have. Plan backwards from what you want your year 9s to know, understand and be able to before they move into their GCSE years. Think about what experience you want your year 9s to have had.

I want our year 9s to have read some great literature and really know the plot, theme and characters of those stories. I want them to own some of that language and be able to use it in conversations about great works of literature or get literary allusions because we’ve given them that cultural capital. I want them to understand that the contexts in which texts are written is important. I want them to know why George Orwell wrote a dystopian novel about totalitarian regimes, I want them to know why Romeo is hopelessly infatuated with a completely unattainable woman at the start of they way and I want them to know why, in her poem ‘Stealing’, a young thief makes off with a snowman in the night.

I want them to be able to write creatively, imaginatively and convincingly – I want them to be able to make people like me laugh out loud or cry (for the right reasons) because their writing is that powerful. I want them to read regularly and be able to use sophisticated vocabulary to express nuanced ideas.

So I want a lot of my students and why not? These students of mine, and yours, get one shot at this and there’s a moral imperative to do what we can to make sure that we’re setting them up for life.

In Part 2 I’ll share how all those wants form the basis of my KS3 curriculum redesign.

This is ggreat

LikeLike